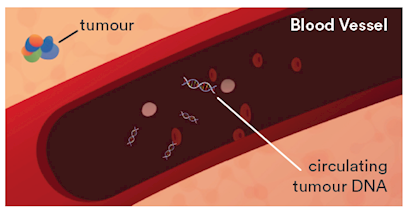

Early detection has been called the ‘Holy Grail’ of cancer management, and thanks to a new widely accessible monitoring test, more clinicians are now able to detect cancer biomarkers in blood earlier than they could using conventional methods.

|

Dr Prasad Cooray is a specialist oncologist with consulting rooms at several locations in Melbourne’s |

In this article, Dr Cooray draws on his experience and elaborates on why he believes the Aspect Liquid Biopsy test will soon become a cornerstone in modern patient care.

Almost by default, as a medical oncologist, you are entrusted with the responsibility of completely coordinating your patient’s journey of care. You oversee timing, you guide clinical approach, and you are

responsible for all systematic treatments more generally, whether they are adjuvant or more advanced – for example, chemotherapy and biological treatments.

Recently, the Aspect Liquid Biopsy test became available, and now its benefits are accessible to oncologists throughout the community.

Particularly in the oncology field, we know that liquid biopsy tests have been around for quite a while – in fact, a number of Melbourne researchers have been at the forefront of their development. I specifically point to Dr Jeanne Tie, who led some pioneering studies three or four years ago demonstrating the tests could be a very useful indicator of early relapses in cancer patients.

However, despite the encouraging nature of these results, only recently have oncologists been given the opportunity to integrate this clinical tool in the care they offer patients.

It was one of those things that sounded good theoretically, and researchers were in the midst of realising its efficacy, but clinicians just didn’t have access to it.

The awareness of the liquid biopsy test is growing within the industry, and more oncologists are not only learning about it but also relying on it in their day-to-day practice. We are very fortunate that the Aspect Liquid Biopsy test is now available to provide a non-invasive accurate and sensitive detection of the circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) in patients’ blood.

Clinical utility of Aspect Liquid Biopsy

How I use Liquid Biopsy with patients obviously changes on a case-by-case basis, but I have personally found that it lends itself to certain cancer types. For example, the test is a useful tool for patients with pancreatic cancer, as 90-95% of this patient population have the KRAS mutation.

Recently, I was part of a clinical trial where we looked at patients having liquid biopsies before their pancreatic cancer operations and then post-procedure, during their follow-up phase. It showed that people who still had circulating tumour DNA post-operation were at much higher risk of cancer relapse down the track. The liquid biopsy test results helped us to select a subgroup of patients who would then undertake chemotherapy. That’s one scenario that I think highlights the benefits of Liquid Biopsy. Ideally, you would want to conduct a preoperative biopsy and then a postoperative one, so a baseline is established. However, we sometimes don’t get the benefit of doing a preop test because the patient may have already had the procedure by the time they come and see us clinically. However, I will always test them post-procedure. It helps me stratify their risk. And down the track, once all treatments are concluded, it acts as an extremely useful surveillance monitoring device as well.

Besides those with pancreatic cancer, I have also found Liquid Biopsy tests extremely useful for lung cancer and colorectal cancer patients, respectively.

The former, because the test picks up any resistant mutations emerging; and the latter (especially in stage 2 or 3), because this is usually the time that, as a clinician, you are deciding whether the patient needs adjuvant therapy or not.

In colorectal cancer, one of the limitations is having no KRAS mutation, meaning that the probability is not as high as in pancreatic cancer, for example. In those mutation negative cases, it’s a wild type – meaning we have to rely on the circulating tumour DNA level and see how the levels correlate up or down with regards to treatment, rather than actually following a mutation.

Liquid Biopsy gives us another tool in our armament, which fuels our clinical decision-making. Additionally, for those cancer sufferers undergoing aggressive treatment with the aim of cure, these tests are a useful device to gauge how the cancer is responding to treatments, and to detect minimal residual disease and potential relapses.

“Without a doubt, I think Liquid Biopsy

will become a standard part of oncology

treatment in the future.”

A patient-specific approach

When I have a patient whom I think could benefit from a Liquid Biopsy, I inform them of the tool, its efficacy and the associated costs. I also pick the time and point where we should do it and lay out a plan for them. For example, in pancreatic patients, I suggest they undertake the test postoperatively so we get a baseline result that I can then use for monitoring down the track. We know that DNA is cleared from the blood fairly quickly, so fortunately, we can pursue this as little as a week following procedure.

Most patients, following our discussion, see the utility of the test and are happy to self-fund. Generally, people see it as another test that is on their calendar, like a scan. Most are relieved it’s just a simple blood test.

However, I contend that the utility of Aspect Liquid Biopsy becomes clearly evident when one undertakes a series of tests. There is just so much utility in continuing the testing and knowing what comes up in scans.

For example, let’s say you treated someone with curative intent and you reached a very low level of circulating DNA. Further, it was an aggressive cancer to begin with, and the patient has a high risk of relapse. In this case, you may want to do a Liquid Biopsy every six weeks, or at least every two months. Of course, one must be mindful of the fact that each case is variable and multiple factors come into play.

The future of Liquid Biopsy

Without a doubt, I think Liquid Biopsy will become a standard part of oncology treatment in the future. I’m expecting the costs will go down in time as well, so I would expect it to become quite an important tool for oncologists in every stage. I think the real future lies in it being a screening test in the population – there is just a huge opportunity there, our “secret weapon” in the early detection of cancers.

Aspect Liquid Biopsy is only available at Australian Clinical Labs.

Expert pathologist

|

Assoc. Prof. Mirette Saad MBBS (Hons), MD, MAACB, FRCPA, PhD Lab: Clayton Areas Of Interest: Molecular Genetics, Cancer Genetics, Antenatal Screening, NIPT, Endocrine, Fertility Testing and Research, Medical Teaching Speciality: Chemical Pathology Phone: 1300 134 111 Email: mirette.saad@clinicallabs.com.au |

Associate Professor Mirette Saad is a Consultant Chemical Pathologist and the National Clinical Director of Molecular Genetic Pathology at Australian Clinical Labs. Upon receiving the National Health and Medical

Research (NHMRC) Scholarship in 2006, Associate Professor Saad commenced her PhD studies at Melbourne University and Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute in Cancer Genetics. Associate Professor Saad undertook her specialty training at Healthscope Pathology (now Australian Clinical Labs) and Monash Health and obtained the Chemical Pathology Fellowship (FRCPA) and the Membership (MAACB) by examination from the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RCPA) and the Australasian Association of Clinical Biochemists (AACB), respectively.