By Dr Sudha Pottumarthy-Boddu and Dr Linda Dreyer

Published May 2023

Every winter respiratory virus season is unique, especially influenza trends. Well-established influenza surveillance systems all over the world aim to gauge, predict, report and ultimately provide guidance for protection (vaccine development) for the upcoming influenza season. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic adds another layer of complexity in making an accurate clinical diagnosis of winter respiratory illness, necessitating a robust, multiplex respiratory PCR assay to enable accurate and timely diagnosis and pathogen-directed specific therapy.

Accurate and timely diagnoses of winter respiratory illnesses strengthen antimicrobial stewardship

By Dr Sudha Pottumarthy-Boddu

How COVID-19 has influenced antimicrobial resistance

The 2022 Special Report COVID-19 U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance1 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports on the impact of the pandemic on alarming trends in antibiotic resistance and on antibiotic prescribing practices.

The number of hospital onset-infections due to resistant pathogens increased by at least 15% from 2019 to 2020 (13% increase for MRSA to 78% increase for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter sp.).

The pandemic also impacted antibiotic prescribing, where antibiotics were often the first treatment prescribed for any febrile pulmonary illness, which often turned out to be COVID-19, a viral illness where antibiotics had no effect.

The importance of preserving and prolonging the efficacy of the currently available antibiotics by being responsible antibiotic stewards is emphasised.

The latest Australian influenza statistics for 2023

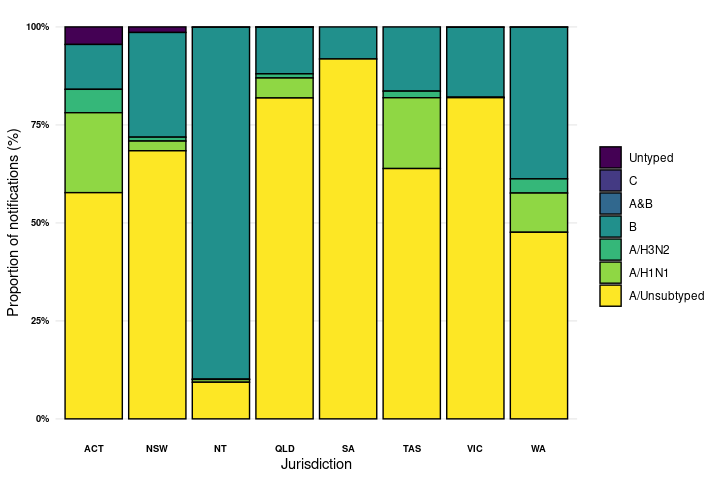

Figure 1. Percent of notifications of laboratory-confirmed influenza, Australia, 1 January to 30 April 2023, by subtype and state or territory* 2

The Australian Influenza Surveillance report for reporting weeks 16 and 17, 2023, notes 32,047 laboratory-confirmed influenza cases, with 32 influenza-associated deaths identified in the year-to-date in the NNDSS (National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System).2 Of the laboratory-confirmed influenza cases, 77% were influenza A (94% influenza A (unsubtyped)) and 22.5% were influenza B (see Figure 1). The number of laboratory-confirmed notifications year-to-date is higher than the 5-year average, but community influenza-like-illness (ILI) activity remains within the historical ranges, with the highest notification rates among the 5-9 year age group, followed by the 0-4 years and 10-14 years age groups.

Given the rising number of influenza notifications in Australia in 2023, in the face of resumed worldwide travel and limited social restrictions, the trends of winter respiratory illnesses remain largely unpredictable at this time.

The use of the multiplex respiratory PCR assay allows for an accurate and timely diagnosis of respiratory viral illness, early administration of appropriate antivirals if indicated and at the same time limits the unnecessary use of antibiotics.

Respiratory Multiplex PCR Testing at Clinical Labs

Visit our Respiratory Testing pages for state-specific ordering instructions.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). COVID-19 & Antibiotic resistance.

Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/covid19.html.

2. Australian Government

Department of Health, 2023. Australian Influenza Surveillance Report 2023 [Report no. 02]. Available

at:

[https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/aisrfortnightly-report-no-2-17-april-to-30-april-2023?language=en]

[Accessed Date: May 10 2023].

The Resistant and the Resilient: Antibiotics in aged care

By Dr Linda Dreyer

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as one of the principal public health problems of the 21st century.

With a rapidly growing aging population, Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACFs) are becoming an increasingly important part of the healthcare system. RACFs are also recognised as an important community setting for monitoring antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use. The high prevalence of infections and colonisation caused by antimicrobial-resistant organisms is well-known in residents of these facilities.

Growing concern over antimicrobial resistance

The 2019 Aged Care National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey highlighted concerning levels of inappropriate antimicrobial use and the resultant increase in the potential for antimicrobial resistance. Alarmingly, about 40–75% of antibiotic use in RACFs has been considered inappropriate. Common clinical indications reported were cystitis, skin, soft-tissue, or mucosal infections, and non-surgical infections. 20% of antimicrobials were prescribed for prophylactic use (rarely recommended), and one-third of all prescriptions were for topical antimicrobials (indicated for a limited number of conditions).

General Practitioners (GPs) have an important role as antimicrobial stewards as they are the key prescribers of antibiotics in outpatient settings.

Managing infection in aged care

Managing RACF residents presents a whole set of challenges for GPs, as patients tend to be prone to infection due to factors such as advanced age, poor functional status, the presence of multiple co-morbidities, compromised immune systems, and the use of urinary tract catheters and other invasive devices. Other challenging factors that affect the decision to prescribe antibiotics are difficulties in establishing symptoms due to cognitive impairment, language barriers, and frequent staff turnover.

The symptoms of infection in the elderly can be very nonspecific and can present as delirium, functional decline, falls, and behavioural changes, usually in the absence of fever. In these scenarios, empirical antimicrobial therapy is often initiated without adequate pathology investigations.

Consequences of inappropriate antibiotic use in aged care

- Increased antibiotic resistance

- Adverse drug reactions and drug interactions

- Clostridioides difficile infection

- Increased healthcare costs

- Diminished quality of care

Areas of concern in prescribing

| Antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria | - In 2018, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) found that

2% of all prescriptions in aged care were for asymptomatic bacteriuria - Four out of five of these prescriptions were for prophylactic antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria - Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common in the elderly and is defined as the growth of organisms at specified quantitative counts (≥105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL or ≥108 CFU/L) in an adequate urine specimen, in patients without symptoms consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI) - It is diagnosed when urine samples are sent for microscopy and culture for patients who do not have clinical symptoms of UTI - It only requires treatment in very limited circumstances |

| Widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics for UTI | - This is rarely indicated, and in the absence of infection risk, prolonged antibiotic use selects for resistant organisms |

| Empiric antibiotics without microbiological investigation | - Causative agents should be identified, especially in symptomatic UTIs |

| Widespread antibiotics prescribing for URTI and chronic bronchitis | - Differentiation between viral and bacterial origin of presumed RTI is essential to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use |

| Prolonged duration of antibiotic treatment | - Risk of side effects and resistance are increased |

| Widespread use of quinolones as empirical therapy for UTIs | - High levels of resistance to quinolones were detected in aged care and should not be used as first-line treatment |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment for elderly residents with advanced dementia or end-stage illness | - Antibiotic therapy is controversial for residents with advanced dementia and may be best guided by advance care directives |

Recommendations for improved prescribing practices

- Adhere to clinical guidelines

- Implement antimicrobial stewardship programs (AMS)

- Educate staff, patients, and families

- Encourage diagnostic testing

- PCR for Respiratory viruses/SARS-CoV2

- Sputum/throat microscopy and culture

- Urine when symptomatic - Regularly reassess and de-escalate therapy

References

Lim, C. J., Stuart, R. L., & Kong, D. C. (2015). Antibiotic use in residential aged care

facilities. Aust Fam Physician, 44(4).

Fact Sheet – Asymptomatic bacteriuria – 2020 |

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care

Baur, D., Gladstone, B. P., Burkert,

F., Carrara, E., Foschi, F., Döbele, S., & Tacconelli, E. (2017). Effect of antibiotic

stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonization with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and

Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious

Diseases, 17(9), 990-1001.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2019).

AURA 2019: Third Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health.

https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/AURA-2019-Report.pdf

Australian

Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2021). AURA 2021: Fourth Australian report on

antimicrobial use and resistance in human health.

https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-09/aura_2021_-_report_-_final_accessible_pdf_-_for_web_publication.pdf

Australian

Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (2022). Antimicrobial stewardship.

https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/antimicrobial-stewardship

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.