GP Connect is an initiative to facilitate a broader understanding of laboratory testing by focusing on common enquiries between General Practitioners and Pathologists at Australian Clinical Labs.

In this edition, Skin Cancer Practitioner Dr Emily Shaw asks Clinical Labs Anatomical Pathologist, Dr Gabriel Scripcaru, a series of questions to promote discussion between general practitioners and pathologists to optimise skin cancer management.

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru

(Pathologist - Australian Clinical Labs, Clayton)

FRCPA, MD

Speciality: Anatomical Pathology

Areas Of Interest: Skin Pathology,

Head, Neck & Soft Tissue Pathology

Phone: 1300 134 111

Email: gabriel.scripcaru@clinicallabs.com.au

Prior to training in anatomical pathology, Dr Gabriel Scripcaru trained in surgery and obtained a membership of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd). Dr Scripcaru’s training in anatomical pathology included rotations at the The Royal Melbourne Hospital, The Royal Women’s and The Royal Children’s hospitals in Melbourne. Before joining Australian Clinical Labs, Dr Scripcaru worked at Southern Sun Pathology in Sydney where he gained experience in dermatopathology.

Dr Emily Shaw

(Skin Cancer Practitioner - Western

Skin Institute, Waurn Ponds and Colac)

MBBS(Hon 1), FRACGP, Advanced

Certificate in Skin Cancer Medicine,

Surgery and Dermatoscopy

Dr Emily Shaw is a full time skin cancer practitioner, working at Western Skin Institute in their Waurn Ponds and Colac clinics. She works under Medical Director, Dr Eugene Tan, specialist Dermatologist and Fellowship accredited Mohs Surgeon, based at the St Albans clinic. Dr Shaw is passionate about ongoing education and is actively involved in GP registrar and medical student teaching. She strongly believes in a collaborative medical approach to patient care and that in skin cancer management, a clinical-pathological correlation is extremely important.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

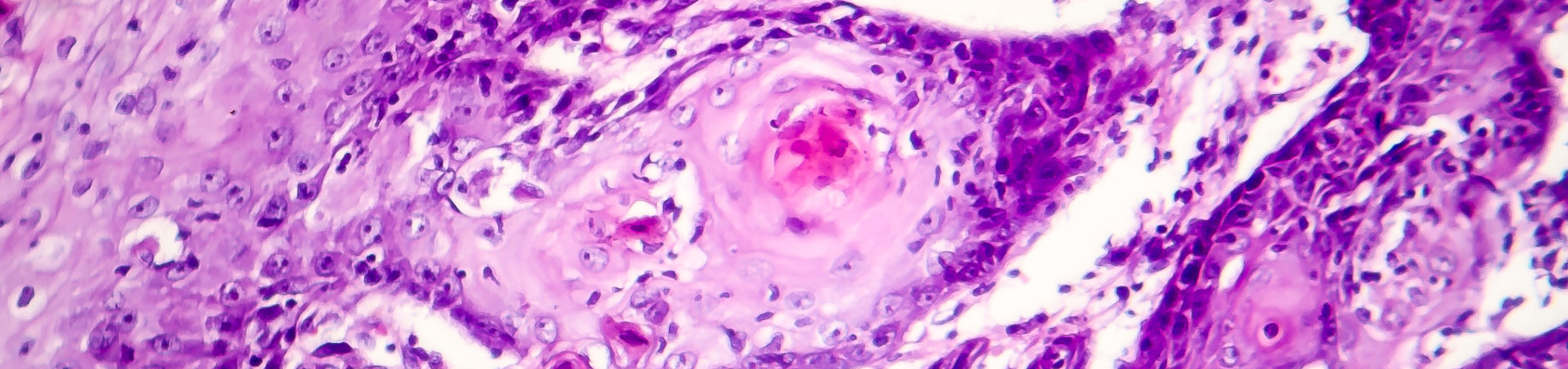

Can you explain what a basosquamous carcinoma is and what the patient implications are for this diagnosis?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

A basosquamous carcinoma is essentially a variant of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) including some areas of basaloid differentiation. It has a propensity to lymphovascular invasion, as opposed to a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or a well differentiated SCC.

The management, staging and follow up should be those of a moderately differentiated SCC.

The diagnostic pitfall, if inadequately sampled (e.g. punch biopsy), is that it may be misdiagnosed as a BCC.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

When we are considering management of an SCC, there are both patient factors as well as histological features in determining a high risk state. Can you explain the histological features which are considered high risk in an SCC?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

High risk histological factors in SCC consist of the following:

1. Low degree of differentiation: increased cytological atypia and nuclear pleomorphism.

2. Degree of keratinisation: reduced or absent keratinisation.

3. Proliferative index: increased mitotic count and presence of atypical mitotic forms.

4. Architectural pattern: highly infiltrative pattern.

5. Presence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion.

6. Certain types of differentiation of the malignant cells: spindle cell/sarcomatoid, basaloid/basosquamous, adenosquamous and desmoplastic.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

Curettage is often a treatment option for some superficial skin cancers. Can you explain the limitation in receiving curetted tissue fragments versus a shave/saucerisation for interpretation?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

Curettage is an adequate procedure in certain clinical scenarios, however, it poses some limitations concerning the histological assessment of the tissue received.

The interpretation of curetted lesions may be hampered by fragmentation of the tissue examined. Fragmentation precludes accurate assessment of the architecture of the lesion. The variable size and multitude of the tissue fragments prevents orientation during embedding and sectioning of the blocks prior to staining of the slides. This leads to inadvertent tangential sectioning. Visualisation of the basal aspect of epithelial structures may mimic lack of “cytological maturation” hence falsely raising suspicion of malignancy.

In addition, crush, cutting or staining artefacts are more likely in fragmented, curetted material.

The pathologist bears in mind all these pitfalls when interpreting curetted specimens. The report and final conclusion may be more guarded when, due to the above mentioned reasons, the presence or absence of a lesion cannot be unequivocally proven or excluded.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

Can you discuss specimen orientation and the implications of a report stating e.g. positive at the 3 o’clock margin?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

Orientation should be attempted only on excisional specimens that are usually elliptical, ovoid or triangular in shape. Orientation of shave and punch biopsies is inadequate and should not be employed.

For clinical reasons, such as wound healing and pathological interpretation, the excisional specimen should have, where possible, a long axis. This is the reason why the most common excisional specimen is ovoid or elliptical.

The orientation allows the pathologist to measure the distance to the respective side of the imaginary clock. A positive 3 o’ clock margin should be read as “the lesion extends to the margin along the 12-3-6 side of the clock”. This may coincide with the 3 o’clock point, but it may be closer to 2 or 4 o’clock. In most specimens it is neither practical, reliable or beneficial to attempt a more detailed description of the margin, as re-excision along the entire involved quadrants of the clock should be employed.

In rare cases, when the specimen is very large and several slices are obtained of which only a small area is involved, a more detailed estimate, such as “3 o’clock towards the 6 o’clock tip of the ellipse” may be given. In this case it allows for a smaller re-excision specimen centred around the previously involved margin.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

Do you find receiving dermoscopic images helpful for slide interpretation?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

Yes, especially in difficult cases or cases where the clinical impression and histological findings do not readily concur. Seeing the dermoscopic image may help in explaining diagnostic conundrums and making a better, more informed diagnosis.

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

I understand that pigmented skin lesions can, at times, be difficult to interpret. As clinicians, what can we do to assist?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

In pigmented lesions, more than in any other neoplastic skin lesions, accurate and detailed clinical information is relevant.

Aspects ideally included are:

- Site of lesion, age of lesion (approximate time of onset), recent change (at clinical routine follow up or noted by patient)

- Clinical description of the lesion, dermoscopic findings

- Previous biopsy, local trauma, symptoms noted by the patient in regards to the respective lesion

Dr Emily Shaw (Skin Cancer Practitioner)

What is the preferred type of biopsy for a melanocytic lesion?

Dr Gabriel Scripcaru (Pathologist)

For melanocytic lesions, the general rule should be attempting to remove the entire lesion, hence a punch biopsy through the lesion is not adequate.

This is due to the fact that a sampled fragment of the lesion does not allow assessment of the architecture and may not be representative of the entire lesion.

A punch biopsy is only acceptable if the lesion is small and the punch biopsy is broad and excisional.

The preferred method is ideally an excisional skin ellipse or a thick shave biopsy which allows assessment of the architecture.